I've often thought about why a particular vineyard can produce an exceptional wine, whereas the next door plot (with an equally talented winemaker) can only come up with, what I would call, a "meh" bottle. If you'd never had the top rated wine, would you find the other producer's wine acceptable? Quite probably, you would, but I bet the average vineyard owner wished they could be the owner of the prime location. Their wine would be highly reputed, highly priced and in great demand, selling out on release every vintage. A dream site.

Just take a trip back in time before any vineyards were planted by mankind. Vines occurred naturally in the wild, growing everywhere they could, even up trees and the fruit was more likely to be consumed by animals and birds. When the first humans came across grapes they were considered only as a source of sweet-tasting, enjoyable nourishment. The invention of alcohol (in this case, wine made from fermented grape juice) was thought to have been an accident. Someone left their collection of grapes in a place where it got damaged and the skins split, releasing the juice into contact with a "wild yeast" which was local to the immediate surroundings. Hey presto, fermentation started and a low strength "wine" was produced. Humans tried it, really liked it and wanted to replicate the accident. Winemaking, in its first incarnation, was born. The world was forever changed!

So, what makes one wine better than another? There are many factors to consider.

The French have a word for it: "Terroir". Difficult to define, it really covers everything which can effect quality. Site location (including altitude & aspect) which will affect how ripe the fruit can get, is probably the number one consideration. Plants and their fruit need sunshine to ripen and the length of time (and strength) which sunlight interacts with the plant will determine whether full, or partial, ripening occurs during the growing season. Hence, a south-facing slope (in the northern hemisphere) will be sunnier than a north-facing one, and vines growing mid-slope generally receive sunshine for a greater amount of time during the day. Full "phenolic" ripening needs to occur where the pips and skins of the grape are ripe as well as the pulp for a balanced juice to be produced. Unripe, and the tannins will be tough and the acidity can be too high. If over ripe, the acidity will be insufficient and the resulting wine will either taste "flabby", or will require acidification (if allowed). A perfect site will allow ideal ripening conditions with little intervening input needed by either the viticulturist or the wine maker. Sometimes, the vines' canopy of leaves needs cutting back to let in the sunlight to aid ripening and, in some vineyards, a valuable technique is to "green prune" by cutting out the smaller bunches of grapes during the summer months to help concentrate the full development of the remaining fruit.

Then comes the soil in which the vine grows. Many growers believe soil is irrelevant as there are many types found in different locations around the world. Some vines like stony, free draining soil, some like clay where, in hot climates, there's good water retention, and some are better suited to growing in areas defined by its limestone bedrock. It was discovered that the vines needing to work hard to produce quality fruit had their roots going deep into the ground to search for nutrients and water. Vines with an "easy life" produced a large volume of flavourless grapes, making poor wines as a result. Climate is also an essential component for quality. Vines are plants which want to grow. Again, given easy growing conditions, vines will produce too high a proportion of leaves, rather than bunches of fruit, so a climate which is borderline for vine growth is going to make for a potentially better wine. Too hot, or too cold and the vine will suffer. Too much rain and you'll get more rot and unusable fruit. Frost and hail at the wrong moment in the vine's life cycle can cause complete devastation with a vineyard being wiped out. Too windy? Vines like shelter from damaging gusts, but not enough air movement in a vineyard can exacerbate the effect of frost, or cause yet more rot if the vegetation stays damp for too long. So, whereabouts on a given piece of ground can dramatically change the way the vines grow. It's not simple!

Different vines grow at different rates, so picking the right type is essential to match it to a particular plot. But how did anyone ever find out this requirement? A vine native to Italy, for example, is unlikely to be found thousands of miles away from its home, so you'd assume it would always make the best wine. Sometimes, a different species will be more successful than the original, local variety, which might quickly become extinct if its character/flavours aren't appreciated by consumers. Drink local if you want to keep an eclectic and interesting range of wines. I very much believe in the idea of "never drinking the same wine twice". Variety is the spice of life, as they say, and I want to try everything I possibly can.

Let's establish a fact. Great wines have more flavour. They might well be subtle and ethereal, but you can guarantee those which are lauded the most will be growing in ideal conditions and are likely to be treated with the greatest care and attention. Balance in the vineyard, soil life, and a non-chemical approach to vineyard pests will, in most cases, make for outstanding bottles. Organic farming and biodynamic practises are found by many growers to have a positive effect on the quality of their produce and, outside of volume/commercial brands, this is the way that production is developing wines with real site specificity. "Minerality" is a much abused wine term, but it should apply to wines with a unique sense of place. Wines made from the same grape variety, in neighbouring vineyards, can be wildly different in taste purely from a change in sub-soil nutrients which are taken up by the vines' roots. If competing "cover crops" are planted between the rows of vines, the roots will need to go deeper to find the necessary water and nutrients and this enables a healthier environment in which the vines are able to grow. A soil devoid of artificial herbicides, pesticides and insecticides is inherently better for quality. Old fashioned, sustainable farming, really is the way to go!

In the vineyard, biodiversity is encouraged and natural wines with minimal handling are often much more enjoyable to drink than over-worked, chemical enhanced juice.

Be warned, though. Some makers of "natural" wines do take it a bit too far. Unfined and unfiltered, no enzymes or artificial chemicals used in the production process can give you a very unappetising looking glass of wine. Cloudy, dark in colour, with a distinct "tang" to the flavour is not what everyone wants. Fresh and fruity, is more likely to appeal to most. You pay your money...

Many of the world's long-standing, established wine regions have had their vineyard land fully mapped for both elevation, aspect and soil make-up and the best plots are well-known to winemakers and consumers, alike. But, just occasionally, there are areas which get missed. Chablis, for example, is known for having a pocket of vines located within the main appellation which can only be sold as Petit Chablis. This lesser appellation is usually reserved for vines planted at the outer limit of the region where growing conditions are not so highly regarded. It's hard to sell a "Petit Chablis" for the same price as a full "Chablis" as customers expect them to always be cheaper!

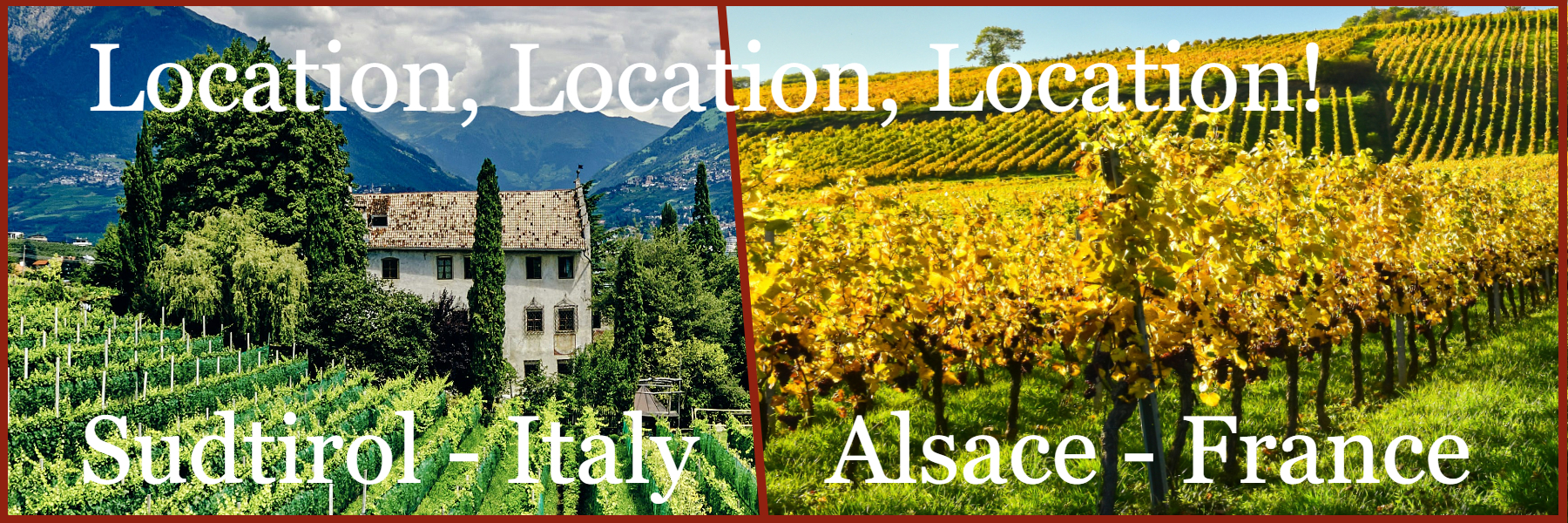

Another example of this is from a producer in Italy's mountainous Alto Adige (Sudtirol) region, Franz Haas. On a visit there many years' ago I was told that a plot of land was purchased where no grower had ever planted vines. It was at very high altitude and was thought to be unsuitable for planting with vines of any kind, but Franz had noticed that this particular site was always the first to lose its snow cover in the Spring because it picked up early morning sunshine. The additional time which the sun shone on this unique location more than outweighed the coolness of the altitude, but kept a perfect level of acidity, enabling long ageing of the wines made from the fruit grown here.

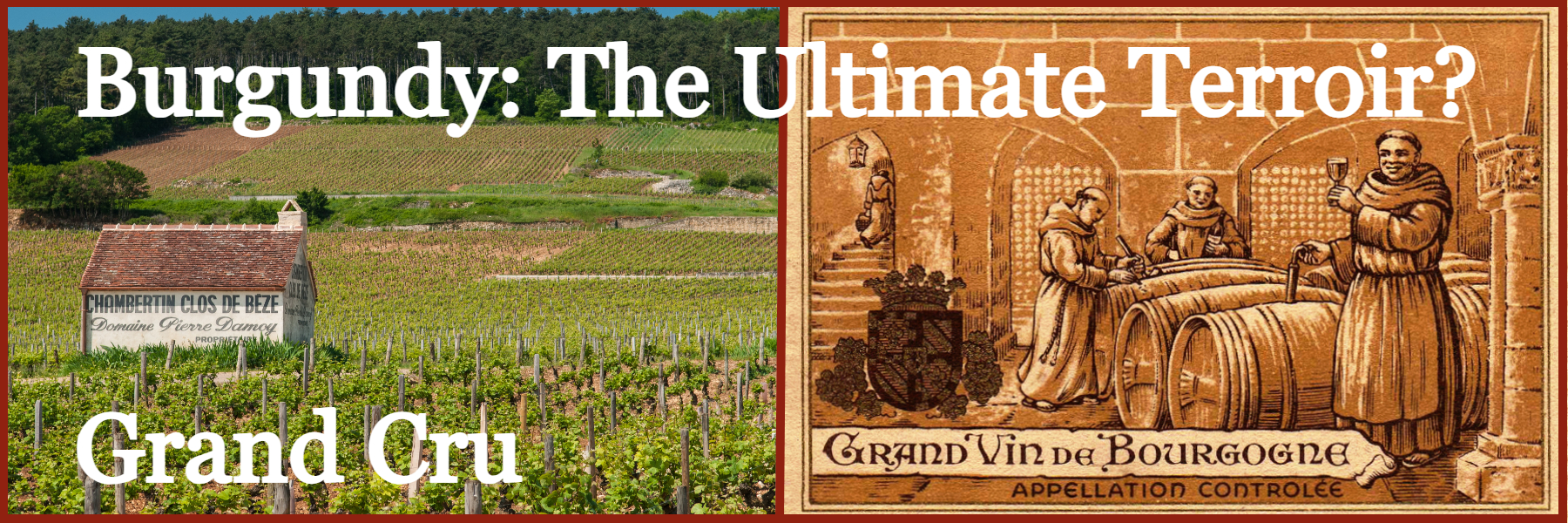

Areas in France, such as Alsace and Burgundy, have long been split into different vineyard gradings. Alsace has its "Grand Cru" designation for the 51 very best sites, where wines made only from the "noble" grapes (Riesling, Gewurztraminer, Pinot Gris and Muscat for whites, with Pinot Noir for red) are allowed. First created in 1983, the Grand Cru appellation has garnered much controversy over the years with much disagreement between various producers who weren't included at the time. Some, who do qualify to use the name, don't, because they consider their individual vineyard names to better known and prefer not to be associated with other "lesser" wines!

Famille Hugel once made a superb single vineyard, dry Riesling which I wished I'd purchased on a trade visit to their quaint location in the town of Riquewihr. Unfortunately, it's no longer produced and the grapes have been used to blend with others. It just tasted perfect to me. A real "terroir" wine. They still make some brilliant Riesling such as the Schoelhammer (£150/bottle) and the Grand Schoenenberg "Grossi Laue" (£50-£70/bottle). Serious money for a Riesling.

Thankfully, the repair work to the sewers in the street outside must have been fixed by now. A truly medieval smell on arrival in the town!

Burgundy is a minefield! So many variations of names from different growers and negociants, individual villages, premier and grand cru sites, it's a lifetime's work to discover all the best wines. If you can afford it, give it a try. A pleasurable way to go, but you'll end up broke before trying all the greatest bottles. You could always sell your car, re-mortgage or sell your house (yes, they can be that expensive). Please keep detailed tasting notes to let your children know where their inheritance went. If you look at the wines of Romanee-Conti, which are 100% Grand Cru rated (costing up to £20,000 a bottle), each appellation they produce is made up of vineyards covering little more than a couple of acres each. The amazing thing is that they all taste completely different. The grape variety (Pinot Noir) is the same in each location. The winemaking is the same. The weather is the same (except for possible localised frost and hail events). So what can be the influence on each wine's taste? It's simply down to the limestone soil. As you move a few yards from one appellation to the next there are subtle changes in the soil make up and the lie of the land. It really does make that much of a difference. Stunning wines, if you get a chance to try any. Luckily, I have, but only once.

Bordeaux makes the identification of the best Medoc & Graves wines a little more straightforward with the "1855 Classification" separating the wheat from the chaff. Based on established prices achieved by merchants at the time, the classification has hardly changed over the last century and a half. With 5 ascending levels of "Classed Growth" properties, along with a lower level "Cru Bourgeois" wines, Bordeaux does adhere to a system which makes reasonable sense to the wine drinker looking for quality. The greatest expressions of Cabernet Sauvignon in the Medoc are found at properties with deep gravel outcrops, located close to the temperature ameliorating Gironde estuary. Yet more evidence of soil and climatic influences having an effect on wine quality in one of the world's most famous wine regions.

Surprisingly, when vines have been growing around the town since Roman times, Saint Emilion eventually got its own "Grand Cru" classification in 1955. Vast amounts of wine are classified with "Grand Cru" status implying the producers have a high opinion of themselves, which isn't always justified! At least, here, the classification is updated every 10 years or so, and chateaux may be up or downgraded. Being typical French farmers, there's often much dispute over this system. Thankfully, the higher levels of "Grand Cru Classé" and "Premier Grand Cru Classé" are a more reliable indication of quality and likely pricing levels. Like most things in life, you get what you pay for, so the £100 bottle will taste considerably better than a £20 bottle, but, if they're gunning for an upgrade, you might just get a bargain.

Germany, with a very long history of fine wine making takes their classification system to the ultimate level of confusion!

Every possible combination of grape type, ripeness level and berry sugar content, region and vineyard location are covered by various technical classifications, with associated groups of "top producers" (e.g. VDP) adding their names to potential representations of wine quality. Don't you just love 'em? Well, yes, at Frazier's we like them all.

With several visits to the varied wine regions of Germany under my travelling belt, it's no surprise that their major white grape, Riesling, can produce astonishing wines from the best vineyards. Some are sweet, but more often these days the wines are dry, with the overriding character being a sense of place. The slate soil of the Mosel's precipitous slopes shines through with a mouth-watering salinity and acidity enabling the wines to age magnificently for many decades. Buy some, keep some, and you'll be amazed at the transformation of flavours and texture from this grape variety. I believe Riesling to be the greatest white grape, bar none. Desert island bottle? What else could there be?

A favourite story from the Mosel was a visit to a small grower based in the town of Piesport. Another area with vineyards dating back to the Romans (who had the knack for spotting the potential for planting a vineyard), this is spectacular wine country. With just a couple of rows of vines located near the top of the ultra steep, south-facing, premier cru (Erste Lage) Goldtropfchen vineyard, the quantity of wine made here wasn't worth bottling, and it was kept for many years in a wooden "foudre" in the cellar for home consumption by the owner. From the outstanding 1976 vintage, and only a "Qba" level wine, it was deep gold in colour and remarkably fresh and alive to taste. Another fabulous Riesling which I couldn't buy, but has stuck in my memory for years. There was only a part full jug and no bottles to take away!

Confusingly, the lesser known, flat Treppchen vineyard, mostly on the opposite (north-facing) bank of the river, used to be planted with potatoes, not vines. Not enough sun exposure and the grapes won't ripen to the same degree and the quality is much lower. And what about the ubiquitous Michelsberg (Grosslage) vineyards, I hear you ask? Vaguely connected to the quality Piesporter wines themselves, this vast production area covers 8 other villages and their wines are usually made from the inferior Muller-Thurgau grape. Unless it's a Riesling, don't bother.

Most other European wine producing regions/countries have variations on different ideas for promoting and highlighting their best vineyards and producers, but I'll leave you with the thought that the rest of the world generally relies on the best wines being the most expensive. It doesn't always work, as there are some winemakers who just overcharge because they hope to be linked with the greatest producers based on nothing other than price. A bit dishonest, in my opinion.

In truth, tastes in wine will always change over time, and wines, once considered the pinnacle of success, drop out of favour and new blood comes to the fore. It's what make wine so interesting... it's constantly evolving, always improving with every vintage.

Now, what will I try next?